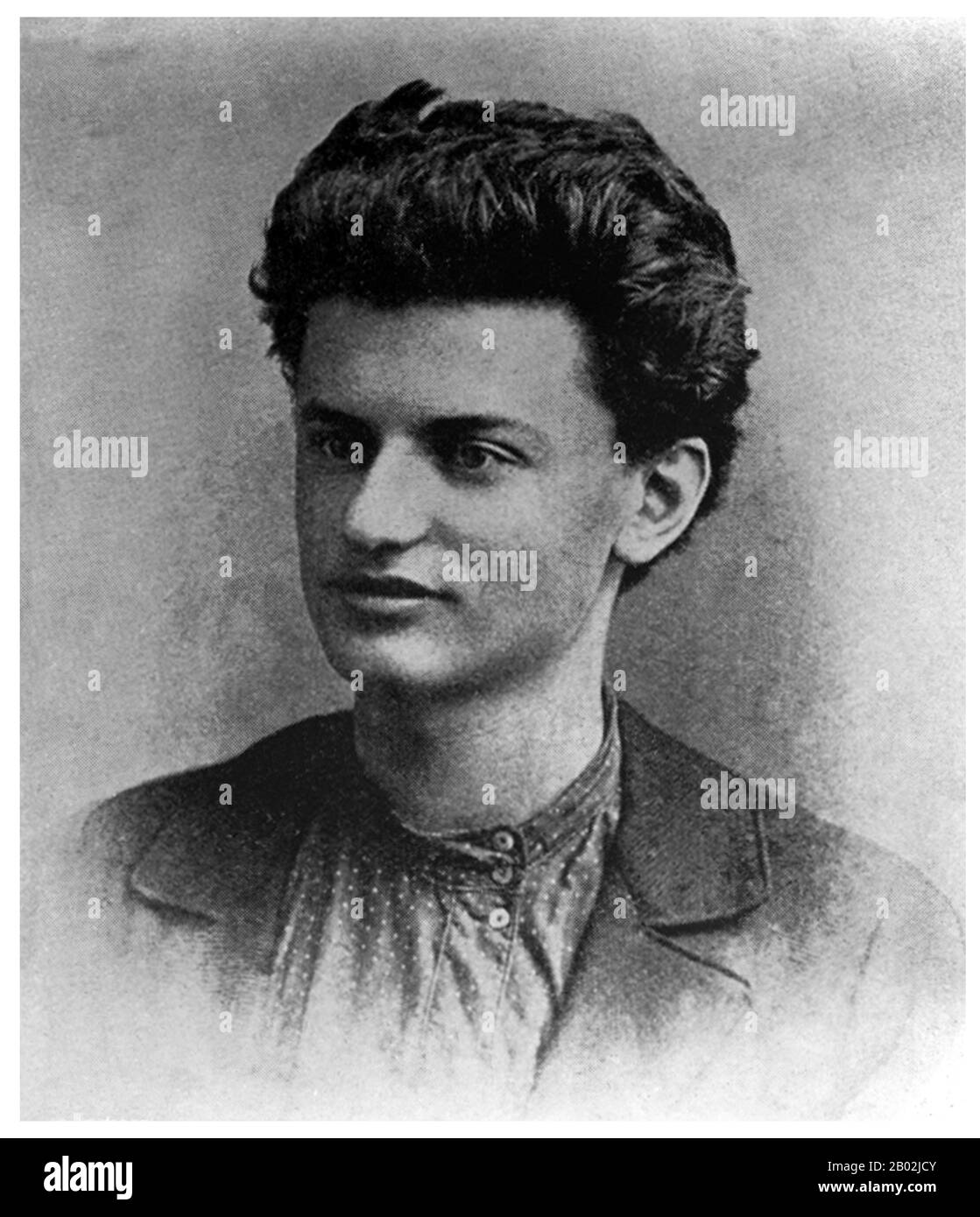

Trotsky Born

| Born | Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río 7 February 1913 |

|---|---|

| Died | 18 October 1978 (aged 65) Havana, Cuba |

| Resting place | Kuntsevo Cemetery, Moscow, Russia |

| Other names | Jacques Mornard; Frank Jackson; Ramón Ivánovich López |

| Occupation | Waiter, militiaman, soldier, agent of the NKVD |

| Spouse(s) | Roquelia Mendoza Buenabad |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | Caridad Mercader, Pablo Mercader Marina |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | 20 years imprisonment |

Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río (born 7 February 1913[1] – 18 October 1978),[2] more commonly known as Ramón Mercader, was a Spanish communist and NKVD agent[3] who assassinated Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky in Mexico City in August 1940 with an ice axe. He served 20 years in a Mexican prison for the murder. Joseph Stalin presented him with an Order of Leninin absentia. His mother participated in the preparation of the assassination, waited for Ramon near the house of Trotsky but escaped to Moscow. With the exception of Ramon Mercader all other persons who participated in the preparation of assassination obtained Soviet awards as well. Ramon was not awarded because nobody could learn how he behaved during the trial and how he would behave in prison.[4]

Mercader was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union after his release in 1961. He divided his time between Cuba and the Soviet Union.

Quietly, series producer Konstantin Ernst has admitted that the series is intended as a “semi-fictional” dramatization, “based on” the character of Trotsky. It’s a rather sinister and reactionary fantasy, born out of the harsh political climate of contemporary Russia. Trotsky got assassinated. Josef Stalin sent Trotsky on a cruise in Mexico but actually hired a hit-men to kill Trotsky in Mexico. When was Trotsky born and where? November 7th, 1879 in Bereslavka, Ukraine. Enjoy the best Leon Trotsky Quotes at BrainyQuote. Quotations by Leon Trotsky, Russian Revolutionary, Born October 26, 1879. Share with your friends.

Life[edit]

Mercader was born on 7 February, 1913 in Barcelona to Eustaquia (or Eustacia) María Caridad del Río Hernández, the daughter of a Cantabrian merchant who had become affluent in Spanish Cuba, and Pau (or Pablo) Mercader Marina (b. 1885), the son of a Catalan textiles industrialist from Badalona. Mercader grew up in France with his mother after his parents divorced. She was an ardent Communist who fought in the Spanish Civil War and served in the Soviet international underground.

As a young man, Mercader embraced Communism, working for leftist organizations in Spain during the mid-1930s. He was briefly imprisoned for his activities, but was released in 1936 when the left-wing Popular Front coalition won in the elections of that year. During the Spanish Civil War, Mercader was recruited by Nahum Eitingon, an officer of the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, an agency preceding the KGB), and trained in Moscow as a Soviet agent.[5]

His cousin, actress María Mercader, became the second wife of Italian film director Vittorio De Sica.

Mercader's contacts with and befriending of Trotskyists began during the Spanish Civil War. George Orwell's biographer Gordon Bowker[6] relates how English communist David Crook, ostensibly a volunteer for the Republican side, was sent to Albacete. He was taught Spanish[7] and also given a crash course in surveillance techniques by Mercader.[8] Crook, on orders from the NKVD, used his job as war reporter for the News Chronicle to spy on Orwell and his Independent Labour Party comrades in the POUM (Workers' Party of Marxist Unification) militia.[8]

Assassination of Trotsky[edit]

In 1938, while a student at the Sorbonne, Mercader, with the help of NKVD agent Mark Zborowski, befriended Sylvia Ageloff, a young Jewish-American intellectual from Brooklyn, New York and a confidante of Trotsky in Paris. Mercader assumed the identity of Jacques Mornard, supposedly the son of a Belgian diplomat.

A year later, Mercader was contacted by a representative of the 'Bureau of the Fourth International.'[9] Ageloff returned to her native Brooklyn in September that same year, and Mercader joined her, assuming the identity of Canadian Frank Jacson. He was given a passport that originally belonged to a Canadian citizen named Tony Babich, a member of the Spanish Republican Army who died fighting during the Spanish Civil War. Babich's photograph was removed and replaced by one of Mercader.[9][10] Mercader told Ageloff that he had purchased forged documents to avoid military service.

In October 1939, Mercader moved to Mexico City and persuaded Ageloff to join him there. Leon Trotsky was living with his family in Coyoacán, then a village on the southern fringes of Mexico City. He was exiled from the Soviet Union after losing the power struggle against Stalin's rise to authority.

Trotsky had been the subject of an armed attack against his house, mounted by allegedly Soviet-recruited locals, including the Marxist-Leninist muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros.[11] The attack was organised and prepared by Pavel Sudoplatov, deputy director of the foreign department of the NKVD. In his memoirs, Sudoplatov claimed that, in March 1939, he had been taken by his chief, Lavrentiy Beria, to see Stalin. Stalin told them that 'if Trotsky is finished the threat will be eliminated' and gave the order that 'Trotsky should be eliminated within a year.'[11]

After that attack failed, a second team was sent, headed by Eitingon, formerly the deputy GPU agent in Spain. He allegedly was involved in the kidnap, torture, and murder of Andreu Nin. The new plan was to send a lone assassin against Trotsky. The team included Mercader and his mother Caridad.[11] Sudoplatov claimed in his autobiography Special Tasks that he selected Ramón Mercader for the task of carrying out the assassination.[12]

Through his lover Sylvia Ageloff's access to the Coyoacán house, Mercader, as Jacson, began to meet with Trotsky, posing as a sympathizer to his ideas, befriending his guards, and doing small favors.[13]

On 20 August 1940, Mercader was alone with Trotsky in his study under the pretext of showing the older man a document. Mercader struck Trotsky from behind and mortally wounded him on the head with an ice axe while the Russian was looking at the document.[14]

The blow failed to kill Trotsky, and he got up and grappled with Mercader. Hearing the commotion, Trotsky's guards burst into the room and beat Mercader nearly to death. Trotsky, deeply wounded but still conscious, ordered them to spare his attacker's life and let him speak.[15]

Caridad and Eitingon were waiting outside the compound in separate cars to provide a getaway, but when Mercader did not return, they left and fled the country.

Trotsky was taken to a hospital in the city and operated on but died the next day as a result of severe brain injuries.[16]

Trotsky's guards turned Mercader over to the Mexican authorities, and he refused to acknowledge his true identity. He only identified himself as Jacques Mornard. Mercader claimed to the police that he had wanted to marry Ageloff, but Trotsky had forbidden the marriage. He alleged that a violent quarrel with Trotsky had led to his wanting to murder Trotsky.

He stated:

... instead of finding myself face to face with a political chief who was directing the struggle for the liberation of the working class, I found myself before a man who desired nothing more than to satisfy his needs and desires of vengeance and of hate and who did not utilize the workers' struggle for anything more than a means of hiding his own paltriness and despicable calculations ... It was Trotsky who destroyed my nature, my future and all my affections. He converted me into a man without a name, without country, into an instrument of Trotsky. I was in a blind alley ... Trotsky crushed me in his hands as if I had been paper.[9]

In 1940, Jacques Mornard was convicted of murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison by the Sixth Criminal Court of Mexico. His true identity as Ramón Mercader eventually was confirmed by the Venona project after the fall of the Soviet Union.[17]

Ageloff was arrested by the Mexican police as an accomplice because she had lived with Mercader, on and off, for about two years up to the time of the assassination. Charges against her eventually were dropped.

Release and honors[edit]

Shortly after the assassination, Joseph Stalin presented Mercader's mother Eustaquia Caridad with the Order of Lenin for her part in the operation.[18]

After the first few years in prison, Ramon Mercader requested to be released on parole, but the request was denied by the Mexican authorities. They were represented by Jesús Siordia and the criminologist Alfonso Quiroz Cuarón. In 1943 Caridad Mercader applied to Stalin personally for her part in the secret operation to release Ramon Mercader.[19] In 1944 she obtained a permit to leave the USSR. However, contrary to the agreed upon conditions, she not only led the attempt of release of Ramon at a distance, but traveled to Mexico, where she was known if not as the mother of Ramon, but as the organizer of the assassination. That undermined an undercover operation that was being prepared to get Ramón Mercader out of jail.[20] Caridad Mercader's presence proved to be counterproductive, because she improved the life of Ramon in prison most significantly but the Mexican authorities tightened security measures, causing the Soviets to abandon their efforts to release Ramon. Though Caridad reported very important things to the Mexican authorities, Ramon served 20 years and 1 day in prison (including the time under initial investigation and trial) according to the initial trial.[20] Ramón, who according to his brother Luis never shared his mother's passion for the communist cause,[21] never forgave her this interference.[22]After almost 20 years in prison, Mercader was released from Mexico City's Palacio de Lecumberri prison on 6 May 1960. He moved to Havana, Cuba, where Fidel Castro's new socialist government welcomed him.

In 1961, Mercader moved to the Soviet Union and subsequently was presented with the country's highest decoration, Hero of the Soviet Union, personally by Alexander Shelepin, the head of the KGB. He divided his time between Czechoslovakia, from where he traveled to different countries, Cuba, where he was the advisor of the Foreign Affairs Ministry, and the Soviet Union for the rest of his life. He married a Mexican named Rogalia in prison after 1940 and had two children. They were declared his and his wife's adopted children, the biological children of Spanish Republicans, after his death.[23]

Ramón Mercader died in Havana in 1978 of lung cancer. He is buried under the name Ramón Ivanovich Lopez (Рамон Иванович Лопес) in Moscow's Kuntsevo Cemetery.[2] His last words are said to have been: 'I hear it always. I hear the scream. I know he's waiting for me on the other side.'[24]

Decorations and awards[edit]

- Order of Lenin, 1940 (in absentia)

- Hero of the Soviet Union, 1961

In popular culture[edit]

- In 1967, West German television presented L.D. Trotzki – Tod im Exil ('L. D. Trotsky - Death in exile'), a play in two parts, directed by August Everding, with Peter Lühr in the role of Trotsky.

- Joseph Losey directed the film The Assassination of Trotsky (1972) featuring Alain Delon as Frank Jacson/Mercader and Richard Burton as Trotsky.

- David Ives' play Variations on the Death of Trotsky is a comedy based on Mercader's assassination of Trotsky.

- A Spanish documentary about Mercader's life, called Asaltar los cielos ('Storm the skies'), was released in 1996.

- A Spanish-language documentary, El Asesinato de Trotsky, was co-produced in 2006 by The History Channel and Anima Films as a joint US/Argentine production, and directed by Argentinian director Matías Gueilburt.[25]

- The Trotsky assassination is depicted in the film Frida (2002), with Mercader portrayed by Antonio Zavala Kugler (uncredited) and Trotsky by Geoffrey Rush.[26]

- Trotskyist veteran Lillian Pollak depicted her friendship with Mercader, then known as Frank Jacson, and the assassination of Trotsky in her self-published 2008 novel The Sweetest Dream.[27]

- A 2009 novel by U.S. writer Barbara Kingsolver, The Lacuna, includes an account of Trotsky's assassination by Jacson.

- Cuban author Leonardo Padura Fuentes' 2009 novel El hombre que amaba a los perros ('The Man Who Loved Dogs') refers to the lives of both Trotsky and Mercader.[28]

- The 2016 film The Chosen, directed by Antonio Chavarrías and filmed in Mexico, is an account of Trotsky's murder, featuring Alfonso Herrera as Mercader.

- Trotsky, a 2017 Russian Netflix series, features Konstantin Khabenskiy as Trotsky and Maksim Matveyev as Mercader, referred to in English subtitles as Jackson, a variant of his pseudonym.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Other sources date Mercader's birth on 7 February 1914

- ^ abPhotograph of Mercader's Gravestone

- ^'The New Trotsky: No Longer a Devil' by Craig R. Whitney, The New York Times, 16 January 1989

- ^L. Mlechin, P. Guontiev. The state corporation of killers. //Novaya gazeta. 08.2020

- ^'Soviet Readers Finally Told Moscow Had Trotsky Slain', The New York Times, 5 January 1989.

- ^randomhouse.co.nz-authors Gordon BowkerArchived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine biography in Random House website

- ^'The Spanish Civil War and the Popular Front', lecture by Ann Talbot, World Socialist Web Site, August 2007

- ^ ab'The Guardian's Prism revelations, Orwell and the spooks' by Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln, 13 June 2013

- ^ abcSayers, Michael, and Albert E. Kahn (1946). The Great Conspiracy against Russia. Second Printing (Paper Edition), pp. 334-335. London, UK: Collet's Holdings Ltd.

- ^Hansen, J. (October 1940). 'With Trotsky to the end,' in Fourth International, volume I, pp. 115-123.

- ^ abcPatenaude, Bertrand (2009). Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky, p. 138. London, UK: Faber & Faber

- ^Bart Barnes (27 September 1996). 'Pavel Sudoplatov, 89, dies'. The Washington Post

- ^'The fight of the Trotsky family - interview with Esteban Volkov' (1988), In Defence of Marxism website, 21 August 2006

- ^CNN, (11 July 2005). 'Trotsky murder weapon may have been found'Archived 2005-09-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Deborah Bonello and Ole Alsaker, (20 August 2012). 'Trotsky's assassination remembered by his grandson', The Guardian

- ^Lynn Walsh (summer 1980). 'Forty Years Since Leon Trotsky's Assassination', Militant International Review

- ^Schwartz, Stephen; Sobell, Morton; Lowenthal, John (2 April 2001). 'Three Gentlemen of Venona'. The Nation. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^Don Levine, Isaac (1960), The Mind of an Assassin, D1854 Signet Book, pp. 109-110, 173.

- ^The letter to Stalin of Caridad Mercader.

- ^ abHernández Sánchez, Fernando (2006). 'Jesús Hernández: Pistolero, ministro, espía y renegado'. Historia 16 (in Spanish) (368): 78–89. ISSN0210-6353.

- ^Juárez 2008, p. 107. sfn error: no target: CITEREFJuárez2008 (help)

- ^Mercader & Sánchez 1990, p. 101–102. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMercaderSánchez1990 (help)

- ^Arrigabalacha ABC (Spain): Moscow traces of a Spaniard who murdered Trotsky.

- ^Borger, Tuckman (13 September 2017). 'Bloodstained ice axe used to kill Trotsky emerges after decades in the shadows'. The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^'Documental argentino revive a León Trotsky' ('Argentine documentary revives Leon Trotsky'), El Mercurio, 12 August 2007 (in Spanish)

- ^'Frida' in IMDBase

- ^Pollak, Lillian. The Sweetest Dream: Love, Lies, & Assassination; iUniverse; May 2008; ISBN978-0595490691

- ^'El hombre que amaba a los perros' ('The Man Who Loved Dogs') in Toda la Literatura review, 2009 (in Spanish)

Further reading[edit]

- Isaac Don, Levine (September 28, 1959). 'Secrets of an Assassin'. Life: 104–122. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Cabrera Infante, Guillermo (1983): Tres tristes tigres, Editorial Seix Barral, ISBN84-322-3016-2.

- Conquest, Robert (1991): The Great Terror: A Reassessment, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0-19-507132-0.

- Andrew, Christopher; Vasili Mitrokhin (1999): The Sword and the Shield, Basic Books, ISBN978-0-465-00310-5.

- Padura Fuentes, Leonardo (2009): El hombre que amaba a los perros, Tusquets Editores (Narrativa), ISBN978-84-8383-136-6.

- Jakupi, Gani (2010): Les Amants de Sylvia, Futuropolis, ISBN978-2-7548-0304-5.

- Wilmers, Mary-Kay (2010): The Eitingons, Verso, ISBN978-1-84467-642-2.

- International Committee of the Fourth International (1981): How the GPU Murdered Trotsky, New Park, ISBN0-86151-019-4

External links[edit]

- Asaltar los Cielos, Spanish documentary about the life of Ramón Mercader, at IMDBase

The Russian Revolutionary Leon Trotsky was assassinated by a Stalinist agent on August 21, 1940. Many today who are interested in socialism know little or nothing about him. And yet Trotsky was a key leader of the only successful working-class revolution in history—the 1917 October Revolution. In the face of poverty and military attack from imperialist governments, the revolution began to degenerate, giving rise to an oppressive state bureaucracy under Joseph Stalin. Trotsky’s campaign against bureaucratism led to Stalin forcing him into exile, and to the hounding and murder of many of Trotsky’s collaborators, supporters and family members. Here we reprint a pamphlet written in August 1970 by Duncan Hallas, originally published by the International Socialists in Britain. At the end, we offer a list of books worth reading by and about Trotsky.

In May 1940 Leon Trotsky wrote an article entitled Stalin Seeks My Death. It was an accurate forecast. Three months later, on 20 August, the Stalinist agent Ramon Mercador, alias Frank Jacson, drove an icepick into Trotsky’s brain in Coyoacan, Mexico.

The assassination was the last of the wholesale murders by which the Stalinist bureaucracy destroyed the Bolshevik old guard. Rykov, Lenin’s successor as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, was shot. Zinoviev, President of the Communist International in Lenin’s day, was shot.

Bukharin and Piatakov, “the most able of the younger members of the Central Committee,” according to Lenin’s Testament, were shot. Rakovsky and Radek both perished. Tens of thousands of old party members disappeared for ever in Arctic “labor camps.” The militants who made the October Revolution were practically annihilated.

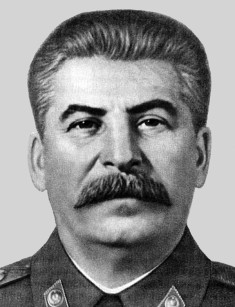

Only one of the leading figures of the years of revolution and civil war survived. Joseph Stalin, the man Lenin proposed should be removed from office as General Secretary, now ruled Russia more despotically than Ivan the Terrible had ever done.

Trotsky’s final verdict on these events was written in the year before his death.

Stalinism had first to exterminate politically and then physically the leading cadres of Bolshevism in order to become that which it now is: an apparatus of the privileged, a brake upon historical progress, an agency of world imperialism.

The hopes of the October Revolution had been buried by the Stalinist terror. There had been no simple counterrevolution. The landowners, capitalists and courtiers of Tsarist times had not recovered their possessions. Stalin founded no dynasty and the leading members of the bureaucracy acquired no legal title to the “public” property. Yet the working people, the officially proclaimed “ruling class,” were deprived of all political rights, even such minimal rights as they had won under Tsarism.

The trade unions had become a machine for disciplining the workforce. And what a discipline. On 28 December 1938, Stalin signed a decree which laid down that “workers or employees who leave their jobs without permission or are guilty of grave offences against labor discipline are liable to administrative eviction from their dwellings within 10 days without any living quarters being provided for them.” The conditions of a 19th century company town were imposed on the workers in the “workers’ state”!

The same decree abolished the right of a worker to a paid holiday after five and a half month’s employment and dealt with bad time-keeping as follows: “A worker or employee guilty of coming late to work, of leaving for lunch too early or returning too late or idling during working hours is liable to administration prosecution.” Managers failing to bring prosecutions “are themselves made liable to dismissal or prosecution.” All this, of course, applied to “free” workers. For the really obstinate offenders there were the labor camps.

Big inequalities in wages were introduced. There was no question of negotiation, of course. Incentive payment schemes became general.

The privileged bureaucrats and managers got bigger and bigger differentials plus the familiar fringe benefits—cars, houses in the country, free holidays in the Crimea and so on. As Stalin said, “We must not play with phrases about equality. This is playing with fire.”

Out of the first successful nationwide workers’ revolution had grown a society that reproduced the inequalities and oppression of capitalism and was ruled by an iron dictatorship, a dictatorship not of the working class but over the working class.

The whole of the latter part of Trotsky’s political life was spent in fighting this reaction, in analyzing it and explaining its causes and in struggling to keep alive the revolutionary socialist tradition against the crushing pressure of Stalinism in Russia and internationally.

Early years

Trotsky was born in the Ukraine in 1879, the son of a Jewish farmer. At that time the labor movement did not exist in the Tsarist empire. In fact an industrial working class hardly existed.

There were a few great nobles, a more numerous lower nobility who officered the army and the state machine, a middle class of merchants, lawyers, doctors and so on and a vast mass of peasants. That was the Russian Empire of the time, and over it the Tsar ruled as absolutely as Louis XIV had ruled France.

There was no parliament, no free press, no freedom of movement, no equality of citizens before the law. Until 1861 the great mass of the Russian people—the peasants—had been legally unfree serfs, unable to leave the estate they were born on, bought and sold by their masters along with the land.

Russia was backward, medieval; so backward that in many ways it was more like France before the great revolution of 1789 than the capitalist countries of western and central Europe.

But a great change was coming. In the years of Trotsky’s boyhood and youth industry was developing fast in Russia, fueled by foreign loans and foreign technicians. New classes were developing, a capitalist class, still much weaker than in the west, and a real industrial working class.

The growth of these classes meant, in the long run, that the Tsarist regime could not last. As late as 1895 the Tsarist minister of finance could write: “Fortunately Russia does not possess a working class in the same sense as the West does; consequently we have no labor problem.” He was already out of date. By 1887 there were already 103,000 metal workers in Russia, by 1897, 642,000. By 1914 there were 5,000,000 workers out of a population of 160,000,000.

This young working class developed a militancy and record of mass struggle unparalleled since the heroic period of the British working class in the 1830s and 1840s. In the early years this century a wave of mass strikes shook Tsarism to its foundations, leading to the explosion of 1905.

A new form of working class self-government, the “Soviet” or workers’ council, was invented by unknown Russian working men. For a time there was a “dual power,” the power of the workers organized in Soviets confronting the panic-stricken government of the Tsar.

The whole regime tottered. But in the end it was able to re-establish its power. The revolutionary workers confronted the peasant army and the peasants were still loyal to the Tsar. A murderous repression followed.

Trotsky grew up with the movement. While still in his teens he joined a revolutionary group in Nikolayev, the South Russian Workers Union. In 1898 he was arrested and kept in various jails until, in 1900, he was deported to Siberia.

In the summer of 1902 he escaped and by the autumn he had joined Lenin in London. By this time Trotsky had become a Marxist and a writer of some fame. Lenin welcomed him and proposed that he join the editorial board of Iskra (Spark), the socialist party paper which was printed in London and smuggled into Russia.

The proposal was vetoed by the senior member of the board, Plekhanov, one of the founders of the party and a future Menshevik. For the split in the Russian socialist party was only a few months ahead and relations between Lenin and some of his co-editors were already tense.

The party at that time consisted of a handful of emigrés in London, Zurich and other European cities and a number of illegal groups of workers and students in some of the Russian industrial centers and in Siberian exile.

The split, which came at the second congress, held in Brussels and then London in 1903, was on the face of it about a comparatively unimportant organizational question. In fact the underlying differences were of vital importance.

Lenin and his group (who became the Bolsheviks, or majority) stood for a tightly organized revolutionary party, able to survive illegality and repression. They believed that only the working class, in alliance with the peasantry, could overthrow Tsarism and “supplant it by a republic on the basis of a democratic constitution that would secure the sovereignty of the people, i.e., the concentration of all the sovereign power of the state in the hands of a legislative assembly composed of the representatives of the people.” (Lenin’s Draft Program of the Social Democratic Party of Russia, 1902).

The minority (Mensheviks) were moving towards the view that the Russian capitalist class could lead this struggle and consequently tended to favor a looser organization oriented to semi-legal work. Neither side supposed that a socialist revolution was possible in a country as backward and under-developed as Russia. That would come later after a period of capitalist economic development under a democratic republic.

In 1903 the differences were not as clear cut as they became later. Not everyone fully understood the implications of the choice they were making. Plekhanov, later leader of the extreme right wing of the Mensheviks, sided with Lenin. Trotsky opposed Lenin. It was a decision he was later to call “the greatest error of my life.”

In 1905 the revolutionary exiles were able to return. Trotsky, now a Menshevik, played a big part in the unsuccessful 1905 revolution. Towards the end of the year he became President of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers Deputies, then the most important workers organization in Russia.

Its liquidation by the reviving Tsarist military and police machine marked the turning point in the revolution. Trotsky was imprisoned again. Put on trial for his life, he defied the Tsar from the dock: “The government has long since broken with the nation … What we have is not a national government but an automaton for mass murder.”

The still smoldering revolutionary movement made the government cautious. The main charge—insurrection—was dismissed. But Trotsky and 14 others were sentenced to deportation to Siberia for life with loss of all civil rights.

In the years of reaction after 1906, the revolutionary organizations, harassed by police spies and unremitting repression, withered and decayed. The Menshevik organizations in Russia virtually disappeared. Even Lenin’s Bolshevik group, now split in to two, a left and a right (with Lenin on the right), shrank into a shadow of its former strength.

Where Was Leon Trotsky Born

In the émigré circles bitter factional disputes developed. Trotsky escaped again from Siberia in 1907 and soon found himself nearly isolated. Repelled by the Menshevik drift to the right and unable to overcome his hostility to the Bolsheviks, he became a lone wolf.

His one positive achievement in these years was the elaboration of his theory of “permanent revolution.” Its central idea was that the coming revolution in Russia could not stop at the stage of a “democratic republic” but would spill over into a workers’ revolution for workers’ power and would then link up with workers’ revolution with the more advanced capitalist countries or be defeated.

It was not so very different from Lenin’s later conception, but Trotsky’s distrust and dislike of Lenin prevented him from joining forces with the only real revolutionary organization – the Bolsheviks.

War and revolution

On 4 August 1914 the world was transformed. The long predicted imperialist war broke out and the leaders of the big social democratic parties forgot about their Marxism and internationalism and capitulated to “their own” governments. The Socialist International broke into pieces.

In every belligerent country, the movement split between the renegades and the internationalists. In September 1915, 38 delegates from 11 countries met at Zimmerwald in Switzerland to reaffirm the principles of international socialism. Trotsky wrote the internationalist manifesto issued by the conference.

There were both revolutionaries and pacifists at Zimmerwald. They were soon to split. The revolutionary nucleus became the forerunner of the Third (Communist) International.

Revolutionary opposition was growing in all the warring states, but it was in Russia that the break came. In February 1917 mass strikes and demonstrations overthrew the Tsar. It was the working-class militants of Petrograd—many of them Bolsheviks—that led the movement.

From the beginning the leaders of the Soviets of workers, peasants and soldiers deputies were in a position to sweep away the crumbling facade of the “Provisional government” and take power. But they did not do so, because they were, in the majority, Mensheviks and Social-Revolutionaries (the peasant party) who believed that a “democratic republic” was necessary to permit the growth of capitalism so as to lay the basis for socialism in the distant future. This meant continuing the war and “disciplining” the workers and peasants.

Even some of the Bolsheviks wavered, notably Kamenev and Stalin, the two central committee members who had escaped from Siberia to take charge of the party in Petrograd. But when Lenin returned in April he would have none of this.

“Down with the Provisional government,” “Peace, Land and Bread” were his slogans. At first a minority in his own party, Lenin won first the party and then the majority of the Soviets for his revolutionary position. It was essentially the same as Trotsky’s “permanent revolution,” and in July Trotsky, together with a group of ex-left wing Mensheviks, entered the Bolshevik Party.

By the autumn the majority of the workers were supporting the Bolsheviks. Under the slogan of “All power to the Soviets,” the Provisional Government was overthrown. In Petrograd hardly a hand was lifted to support it.

The next years were the years of Trotsky’s greatest fame. First as People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs and then as People’s Commissar for War, he was second only to Lenin as the moving spirit of the revolution.

These were the years of revolutionary optimism. Everything seemed possible. Though the Soviet government had to fight desperately against massive foreign intervention—the armies of 14 powers fought against the revolution—and against foreign armed and financed White armies, the whole of Europe seemed on the verge of revolution.

Revolutionary Soviet regimes were actually established in Hungary, in Bavaria, in Finland, in Latvia. The German Kaiser, the Austrian Emperor, the Turkish Sultan were all overthrown.

The whole of Germany seemed on the brink of red revolution. In Italy mass strikes and violent demonstrations paralyzed the capitalist state.

Even the sober Lenin could write in 1918: “History has given us, the Russian toiling and exploited classes, the honorable role of vanguard of the international socialist revolution; and today we can see clearly how far this revolution will go. The Russians commenced; the Germans, the French and English will finish and socialism will be victorious.”

For Trotsky there were no doubts. The “final conflict” was now. When the Third International was founded in 1919 he wrote in his first manifesto:

The opportunists who before the world war summoned the workers to practice moderation for the sake of gradual transition to socialism … are again demanding self-renunciation of the proletariat … If these preachments were to find acceptance among the working masses, capitalist development in new, much more concentrated and monstrous forms would be restored on the bones of several generations-with the perspective of a new and inevitable world war. Fortunately for mankind this is not possible.

In fact the success of the German revolution hung in the balance. The opposing forces were nearly equal. Success would have changed the course of European and world history. Failure meant the eventual triumph of reaction not only in Germany but also in Russia.

Defeat in victory

For the civil war ruined the already backward Russian economy and dispersed the Russian working class. The White counter revolution was beaten because the great majority of the Russian people—the peasants—knew that the revolution had given them the land and that a restoration would take it back again.

Yet by the end of the civil war the workers had lost power because, as a class, they had been decimated. By 1921 the number of workers in Russia had fallen to 1,240,000. Petrograd had lost 57.5 per cent of its total population. The production of all manufactured goods had fallen to 13 per cent of the already miserable 1913 level. The country was ruined, starving, held together only by the party and state machines developed during the civil war.

It was a situation that had not been foreseen. At the time of the Brest Litovsk peace with Germany in 1918 Lenin wrote: “This is a lesson to us because the absolute truth is that without a revolution in Germany we shall perish.” For, of course, there could be no question of the Russian working class, a small minority with a weak economic base, maintaining a workers’ state for any length of time without integrating the Russian economy with that of a developed socialist country.

Later at the third Congress of the Third International in 1921 Lenin returned to the point:

It was clear to us that without aid from the international world revolution, a victory of the proletarian revolution is impossible. Even prior to the revolution, as well as after it, we thought that the revolution would occur either immediately or at least very soon in other backward countries and in the more highly developed capitalist countries, otherwise we would perish.

Notwithstanding this conviction, we did our utmost to preserve the Soviet system, under any circumstances and at all costs, because we know we are working not only for ourselves but also for the international revolution.

By 1921 the international revolution had been beaten back and the communist regime in Russia faced another desperate crisis. The peasant masses, freed from the fear of landlordism were moving into violent opposition. Peasant riots in Tambov, the Kronstadt rising and the strikes in support of it showed that the regime no longer enjoyed popular support. It was becoming a dictatorship over the peasantry and the remnants of the working class.

A retreat was essential. The New Economic Policy, from 1921 onwards, recreated an internal market and gave the peasantry freedom to produce for profit and to buy and sell as they wished. Private production of consumer goods for a profit was also permitted and the publicly-owned large-scale industry was instructed to operate on commercial principles.

The result was a slow but substantial economic recovery, together with mass unemployment—never less than a fifth of the slowly reviving industrial working class—and the development of a class of capitalist farmers, the kulaks, out of the ranks of the peasantry.

By the middle 1920s the economic output levels of 1913 had been reached and in some cases passed. By that time the balance of social forces had altered fundamentally.

What sort of society was emerging? As early as 1920 Lenin had argued:

Comrade Trotsky talks about the “workers’ state.” Excuse me, this is an abstraction. It was natural for us to write about the workers’ state in 1917 but those who now ask “Why protect, against whom protect the working class, there is no bourgeoisie now, the state is a workers’ state” commit an obvious mistake … In the first place, our state is not really a workers’ state, but a workers’ and peasants’ state … But more than that. It is obvious from our patty program that … our state is a workers’ state with bureaucratic distortions.

Since then the “bureaucratic distortions” had grown enormously and the ruling party itself had grown enormously and the ruling party itself had become bureaucratized. In the absence of a working class with the strength, cohesion and will to rule, the party had had to substitute for the class and the party apparatus was increasingly substituting for the party membership.

A new group of “apparatchniks” had grown up alongside the kulaks and the “nepmen” (petty capitalists). Trotsky, in one of his most striking phrases, described politics as “the struggle for the surplus social product.” Between these three groups such a struggle developed over the heads of the mass of the poorer peasants and against the working class.

Challenging the Stalinist Bureaucracy

The struggle was reflected in the ranks of the now bureaucratized party, especially among its leaders. Trotsky, by now thoroughly alarmed at the rightward trend, became the chief spokesman of a tendency that took up the fight, started by Lenin in the last months of his life, for the democratization of the party and the revival of the Soviets as real organs of the workers and peasants.

An essential part of the program of the Left Opposition (as Trotsky’s group was called) was the more rapid and planned development of Russian industry. For Marxists it was out of the question for democratization to succeed without an increase in the numbers, self-confidence and specific weight’ of the working class.

Opposed to the left was a right wing tendency for which Bukharin became the spokesman. This argued for stability, for accumulation “at a snail’s pace,” and for giving priority to keeping the peasantry happy, including the kulaks.

There was a third tendency, the “center”, representing the apparatchniks, the bureaucracy. It was then allied to the right. Its leading figure was J.V. Stalin, an old Bolshevik, a capable organizer and a man of unbounded ambition and iron will.

Stalin was welding the bureaucracy into a class, conscious of its own interests and with its own ideology—“Socialism in a single country.”

The perspective of the opposition was one of peaceful reform. The pressure of events and of the opposition could reform the party and the country, it thought.

In the event, the extent of the bureaucratic degeneration was shown by the ease with which the opposition was defeated. Though it included some of the most distinguished members of the party and was joined, after 1926, by the group around Zinoviev, Lenin’s closest collaborator in exile, and Krupskaya, Lenin’s widow, as well as by the “ultra-left” democratic centralist group, it was overwhelmingly voted down in party meetings packed by Stalin’s yes-men.

In October 1927 Trotsky and Zinoviev were expelled from the party. Soon they arid thousands of other oppositionists began the journey into exile. The opposition had been smashed and from their places of exile its leaders predicted a dire danger from the right.

The Soviet “Thermidor,” the overthrow of the party by the representatives of the kulaks and nepmen, was imminent. And indeed the regime did face a danger from the right. In 1928 the kulaks, encouraged by the liquidation of the left, engineered a “grain strike,” a hoarding operation which faced the cities with starvation. The sequel showed how grossly they—and the opposition—miscalculated the strength of the rival forces.

The bureaucracy executed a violent change of course. After years of appeasing the rich peasants they resorted to forced collectivization, to the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class.”

Under the guise of one-party rule, a narrow clique of bureaucrats ruled Russia. And they were soon to become the puppets of one man. By 1930 Stalin was the new Tsar, in fact if not in form.

With the forced collectivization came a frenzied program of forced industrialization. Schemes far exceeding the most ambitious plans of the most optimistic members of the opposition were put in train, only to be superceded by others still more far-reaching. “Fulfil the five year plan in four years” became the slogan.

The man who yesterday ridiculed the moderate plans of the opposition as utopian now wished to “catch up and outstrip” the advanced capitalist countries in a few years.

The first five year plan did succeed in laying the basis for an industrial society. It did so on the basis of the most brutal exploitation of the workers and peasants. Real wages fell drastically. The draconically regimented “free” workers were supplemented by an army of slave laborers, mostly ex-peasants, employed on large scale construction jobs under appalling conditions. All vestiges of democratic rights disappeared. A fully fledged totalitarian regime emerged.

These events disintegrated the exiled opposition. Many of its most prominent members made their peace with Stalin.

At the other extreme, many rank and file oppositionists came to agree with the “democratic centralists” that a new revolution was necessary. “The party,” wrote Victor Smirnov, a democratic centralist leader, “is a stinking corpse.”

The workers’ state had been destroyed years earlier, in his opinion and capitalism restored. Trotsky would accept neither of these positions. Against the capitulators he insisted on the need for Soviet democracy. Against the left he insisted on the possibilities of peaceful reforms.

It was an unreal assessment and Trotsky was to abandon it 18 months later. The impetus for the change came from events in Germany. The left opposition had been concerned at least as much with the International as with Russia.

The Third International in its early years had been far from being the tool of Moscow. But with the receding of the revolutionary mood in Europe the parties became more attached to the one surviving “Soviet” regime and more dependent on it.

Advice from Moscow became the most important source of their political ideas. Increasingly the Russian, and hence apparatchnik, dominated executive of the International began to interfere with the national life of the parties.

The myth of the “Soviet Fatherland” became more and more important to European and Asian Communists. Gradually the more independent spirits and the more serious Marxists were eliminated from the leaderships. It took 10 years to reduce the world movement to the position of Moscow’s foreign legion. By 1929 the process was complete.

While the right-center bloc ruled Russia the policy of the International was pushed to the right. Semi-reformist policies were promoted and they led to a number of avoidable defeats.

The opposition sharply criticized the Comintern policies and sought to develop contacts with dissident members of the foreign parties. But after Stalin had eliminated his former “rightist” allies in Russia, the Comintern was swung violently to the left, to the lunatic left in fact. A period of “general revolutionary offensive,” the “third period” was proclaimed.

The theory of “social fascism” was invented. The social democratic and labor parties were “social fascists,”groups to the left of them like the ILP were “left social fascists.”

In Germany, where the danger of fascism was very real, this led to the rejection of any joint anti-fascist resistance with the social-democrats and the trade unions under their influence. For these were themselves fascists! In fact everyone who was not a loyal Stalinist was a fascist: “Germany is already living under fascist rule,” said the German Communist daily. “Hitler cannot make matters worse than they already are.”

Against this insane policy Trotsky, from 1929 an exile in Turkey, wrote some of his most brilliant polemics. If reason could have moved the Stalinized leaders of the German Communist Party, Hitler would have been beaten, for the opportunity was there. A victorious united front was possible. But they were beyond reason. The only voice they heard was that of Stalin intoning “Social democracy and fascism are not opposites: they are twins.”

The German workers’ movement was smashed. The Communist Party surrendered without a fight. Hitler came to power and preparation for the Second World War began.

This terrible defeat caused Trotsky to break with the International. “An organization which has not been awakened by the thunderbolt of fascism … is dead and cannot be revived.”

Soon after this he abandoned his reformist position on Russia. A new revolution was necessary to remove the bureaucratic dictatorship.

Yet he did not modify his view that Russia was a “degenerated workers’ state.” For the few years left to him he clung to that abstraction—a “workers’ state” in which the workers were not only not in power but were deprived of the most elementary political rights. It was an error that was to have a lasting and pernicious influence on the revolutionary left.

Trotsky was now nearly alone. Soon after the German catastrophe the great purges began in Russia. Stalin consolidated his personal rule by the mass murder of the former capitulators, of the former rightists and of most of his own early supporters.

All alike were denounced, along with Trotsky, as agents of Hitler, counterrevolutionaries, spies and saboteurs. A series of grotesque “show trials,” at which prominent leaders of the revolution in Lenin’s time were made to confess their guilt—and that of the monster Trotsky.

A climate of opinion was created in which it was impossible for Trotsky to influence left wing workers. “The Stalinist bureaucracy had actually succeeded in identifying itself with Marxism … Militant French dockers, Polish coalminers and Chinese guerrilla fighters alike saw in those who ruled Moscow the best judges of Soviet interests and reliable councilors to world communism.”

The Comintern was now swung rightwards again. Stalin’s foreign policy required an alliance with the “western democracies.” The “popular front”—the subordination of the workers’ parties to liberals and progressive’ Tories—was the new line.

It enabled Stalin to strangle another revolution—Spain. Trotsky called the Spanish defeat “the last warning.” All his energies in the last years of his exile, in France, Norway and then Mexico, were spent in trying to create the nucleus of a new International, the Fourth. Its founding conference took place in 1938 under the shadow of multiple defeats for the working class. Trotsky now had less than two years to live.

It was his imperishable achievement to keep alive the tradition of revolutionary Marxism in the decades when it was all but extinguished by its pretended supporters.

Trotsky was far from infallible. Lenin had written in his testament of Trotsky’s “too far-reaching self-confidence” and it was his misfortune, in his last years, that few among his adherents were capable of independent thinking.

That he towered over his associates was at once his strength and his tragedy. Perhaps no other man could have withstood isolation and attack as he did.

His contribution to revolutionary socialism and to the working class movement was unsurpassed. He was one of the handful of truly great figures the movement has produced.

Appendix

Trotsky’s testament

My high (and still rising) blood pressure is deceiving those near me about my actual condition. I am active and able to work but the outcome is evidently near. These lines will be made public after my death.

I have no need to refute here once again the stupid and vile slanders of Stalin and his agents: there is not a single spot on my revolutionary honor. 1 have never entered, either directly or indirectly, into any behind-the-scenes agreements or even negotiations with the enemies of the working class. Thousands of Stalin’s opponents have fallen victims of similar false accusations. The new revolutionary. generations will rehabilitate their political honor and deal with the Kremlin executioners according to their deserts.

I thank warmly the friends who remained loyal to me through the most difficult hours of my life. I do not name anyone in particular because I cannot name them all.

However, I consider myself justified in making an exception in the case of my companion, Natalia Ivanovna Sedova. In addition to the happiness of being a fighter for the cause of socialism, fate gave me the happiness of being her husband. During the almost forty years of our life together she remained an inexhaustible source of love, magnanimity, and tenderness. She underwent great sufferings, especially in the last period of our lives. But I find some comfort in the fact that she also knew days of happiness.

For forty-three years of my conscious life I have remained a revolutionist: for forty-two of them I have fought under the banner of Marxism. If I had to begin all over again I would of course try to avoid this or that mistake, but the main course of my life would remain unchanged. I shall die a proletarian revolutionary, a Marxist, a dialectical materialist, and, consequently, an irreconcilable atheist. My faith in the communist future of mankind is not less ardent, indeed it is firmer today, than it was in the days of my youth.

Natasha has just come up to the window from the courtyard and opened it wider so that the air may enter more freely into my room. I can see the bright green strip of grass beneath the wall, and the clear blue sky above the wall, and sunlight everywhere. Life is beautiful. Let the future generations cleanse it of alt evil, oppression and violence, and enjoy it to the full.

27 February 1940, Coyoacan

Leon Trotsky Born

Further reading:

Duncan Hallas, Trotsky’s Marxism

When Was Leon Trotsky Born

Leon Trotsky, My Life

Trotsky on Permanent Revolution

Leon Trotsky’s writings on German Fascism

Trotsky Born

Leon Trotsky, Stalinism and Bolshevism